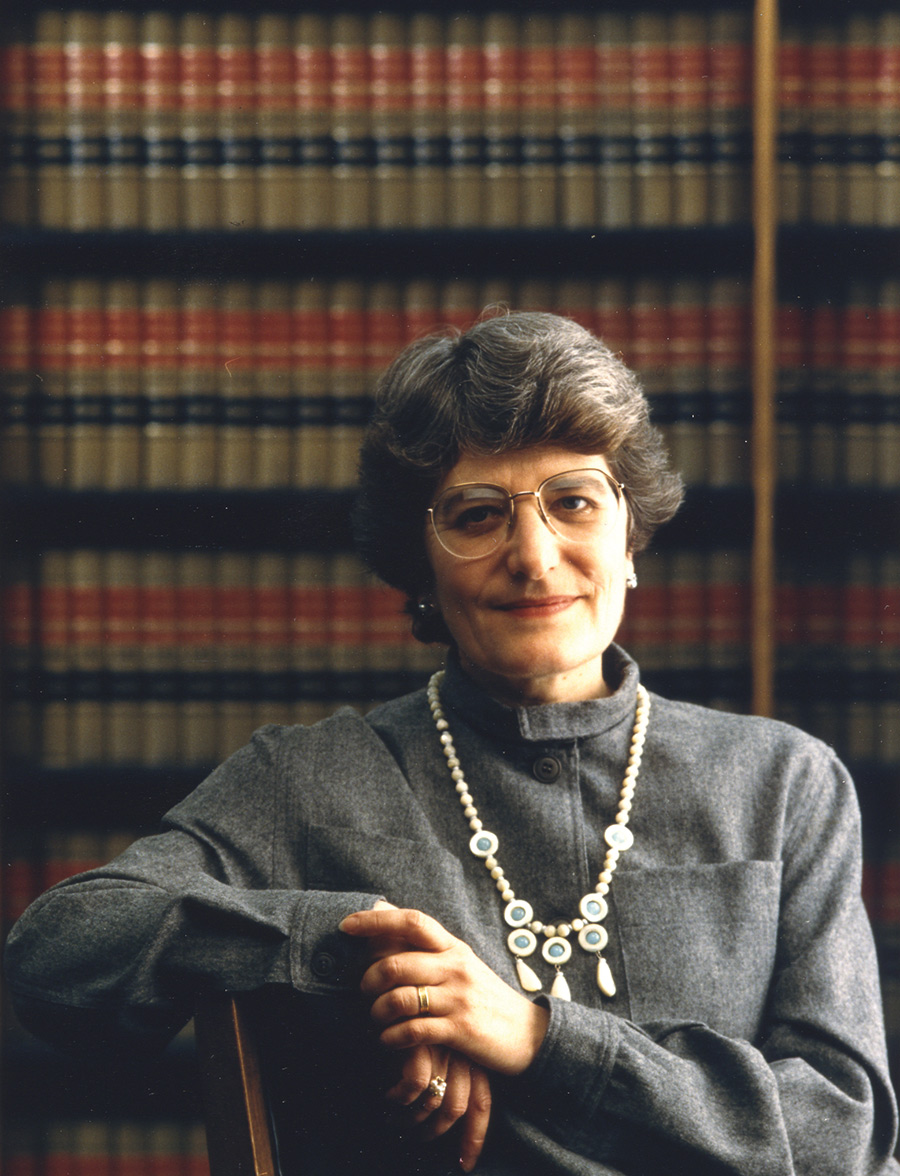

legal scholar, Professor Roberta

Karmel has an impact that resounds

from Washington, D.C., to Wall

Street, to her classroom at Brooklyn

Law School. When her colleagues

shared stories and explored her work

at a May symposium in her honor,

they brought into sharp focus her

enduring legacy and influence—her

relentless drive for excellence and

her deep devotion to her students,

colleagues, and family.

A Career

and Life

at the Center

Portrait by Laura Barisonzi

She had joined Rogers & Wells (now Clifford Chance) in 1972, becoming one of the first female partners at a top Wall Street law firm. Then, after being among the first women on staff at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), she was nominated by President Jimmy Carter to serve as its first female commissioner in 1977. By 1985, she had built a deeply respected career as a leading authority in domestic and international securities regulation, published scholarly journal articles and the book Regulation by Prosecution: The Securities and Exchange Commission Versus Corporate America (Simon & Schuster, 1982), and served on several corporate boards. Yet there was another chapter in her career that Karmel was eager to explore.

She called David Trager, who was then dean of Brooklyn Law School, where she had taught as an adjunct professor in the early 1970s and early 1980s. “It was one of the few law schools hiring women in tenure-track faculty jobs,” Karmel later said. “And I said, ‘David, you’ve always wanted me to go onto the full-time faculty; I have always wanted to be a full-time academic. This is your chance.’”

Thirty-six years later, as Centennial Professor Roberta Karmel announces her retirement from the Law School and begins yet another chapter in her life, generations of her students and colleagues are grateful Trager jumped at that chance.

“Roberta Karmel is a reminder that deans come and go, but faculty define an institution,” said Dean Michael T. Cahill. “Roberta is among those illustrious members of our community who have made Brooklyn Law School what it is today.”

From Chicago to the SEC

That pursuit of excellence forms a long line tracing back to Karmel’s early years in Chicago, where the passion of her youth was studying and teaching ballet. After she earned her bachelor’s degree in history and literature at Radcliffe, a post-college stint at a small brokerage firm in Boston sparked her interest in law. New York University School of Law followed, and after earning her J.D., she was accepted into an honors program at the New York regional office of the SEC in 1962.

Private practice beckoned, and in 1969, she became an associate at Willkie Farr & Gallagher, where she built a thriving practice conducting regulatory work, representing many small broker-dealers. Undaunted by the sexism of the day in the profession, she sought a partnership in private practice and was told by one firm, “While we are ready for female associates, we’re not ready for a female partner.” But she persisted, ultimately becoming the first woman partner at Rogers & Wells in 1980.

Commissioner Karmel

From the start of her tenure as the first woman nominated and confirmed as an SEC commissioner, Karmel was, as her chief counsel John Paul Ketels said, “an activist change agent, not to be denied or deterred.” She was concerned that the agency’s Enforcement Division was taking extreme positions not in accordance with the law, and then settling cases with consent decrees containing relief that no court would or could have ordered. She believed that SEC prosecution should be based on existing law, rather than being used to make new law, and she expressed this position in her votes on enforcement actions.

“What [Karmel] did as SEC commissioner made the SEC think about the way it wields its power,” said Ketels.

During her early years at the SEC, Karmel bucked tradition by having three children while continuing to work. She recalled that many members of the male investigative team thought a mother shouldn’t be working. Not only did she ignore their criticisms, but she also led by example, helping to hire more women as attorneys at the agency.

“I hope I always did a good job so that more women would be appointed to the positions [I had held],” said Karmel in an interview on Professor Andrew Jennings’ Business Scholarship podcast (see box). “I always advise younger women to lead a full life…. Don’t wait to become a partner, don’t wait to get tenure as a professor to round out your personal life.”

Professor, Innovator, Mentor

Joining the Law School as a full-time faculty member in 1985, Karmel quickly became known for her engaging teaching and invaluable mentorship in classes on tort law, securities regulation, corporations, administrative law, and European Union law.

“She showered our securities regulation class with her wonderful wit and insight from her time at the SEC, while also giving us a grounded and practical understanding of the framework of [those] regulations,” said New York County Civil Judge Ilana Marcus ’87. “She was one of the main reasons I became a securities attorney.”

Karmel’s influence extended to the intellectual life of the Law School. She co-founded and co-directed the Dennis J. Block Center for the Study of International Business Law, the Law School’s first academic center (see “Innovation at the Center”). She also developed the Center for the Study of Business Law and Regulation and helped create and expand the Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law.

“Roberta’s biggest contribution to the center is her generosity of leadership,” said center co-director Professor Robin Effron. “For her, it’s about being better and changing to reflect the students.”

The obstacles that Karmel faced early in her career as a woman rising in a then male-dominated profession sparked her lifelong commitment to opening doors for others. In the early days, as she contemplated a career in the law, she recalls her attorney father saying, despite his belief in her abilities, “Why go to law school? You’re a woman. You’ll never get a job.” But her mother, a homemaker, said Karmel, “believed in women achieving what they could in the world,” and encouraged her.

Professor Miriam Baer, one of those to benefit from Karmel’s mentorship, recalls her “willingness to be a sounding board, her ability to see nuance, her fearlessness to do the right thing, and her encouragement of individuality, making her a particularly effective teacher, mentor, and friend.”

Karmel has never relented in her pursuit of fairness and opportunity.

“There’s the saying, ‘speaking truth to power,’” said U.S. Court of International Trade Judge and Law School Trustee Claire Kelly ’93. “Roberta speaks truth to everyone, with a purpose of being helpful. She cuts through the posturing and politicizing to what needs to be done, and makes sense of it. Roberta Karmel fought for us.”

Back Cover

“Roberta Karmel is among those illustrious members of our community who have made Brooklyn Law School what it is today.”

— Dean Michael T. Cahill

A Salute to Karmel’s Impact

In May, Karmel’s colleagues and students past and present gathered to pay tribute to her, as the Law School hosted the virtual symposium A Life Navigating the Securities Markets: A Celebration of Professor Roberta Karmel’s Work, Teaching, and Mentorship. Panel discussions focused on areas of the securities markets in which Karmel has had a significant impact, and an evening celebration was filled with stories from attendees.

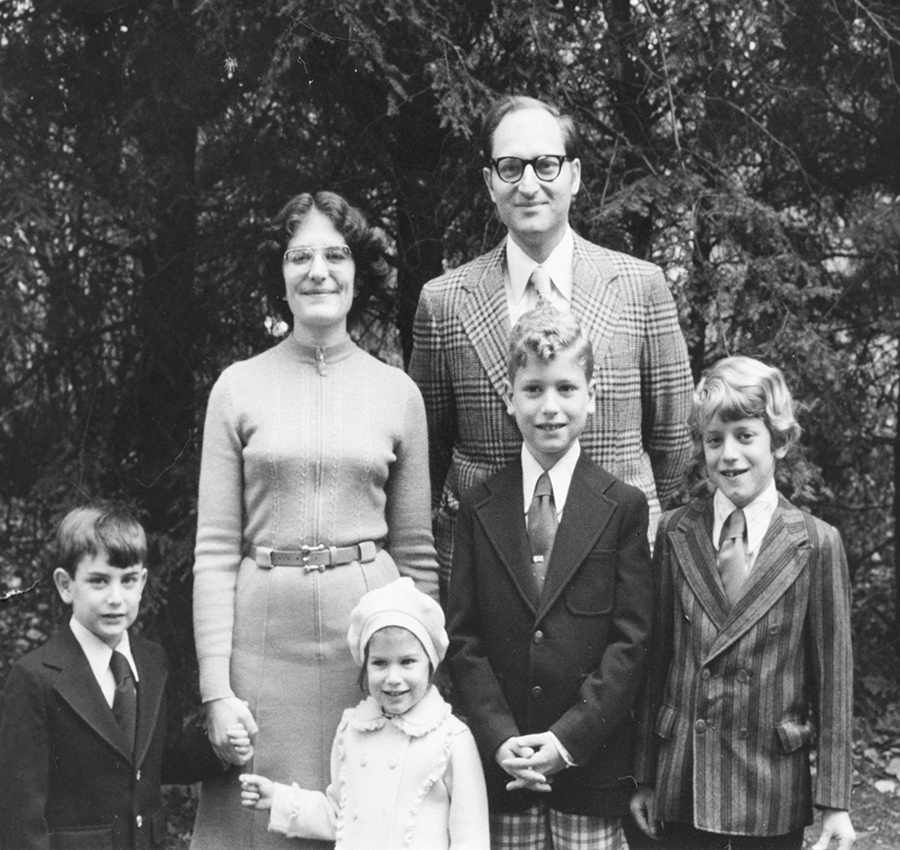

Karmel’s four children, multiple grandchildren, and other family members also joined in the celebration. They recounted Karmel’s passion for sharing cultural events, travel, good conversation, and arguments, and described a lifetime of encouraging their unique abilities, all while honing her own career in securities law. As her son Philip Karmel said, “Like Walt Whitman, Roberta Karmel contains multitudes.”

“Usually when I go to events where I am honored, I receive some beautiful piece of crystal in a lovely box,” Karmel said, in the celebration’s closing remarks. “One day a student came to my office and happened to look into one of those boxes and questioned why there were pieces of glass scattered around the bottom. I told him, ‘It’s simply about breaking the glass ceiling.’”