The

Rise

of

Green

Cities

For legal professionals in finance, land use, and real estate, the move toward a greener future brings endless opportunities.

Illustration by Celyn Brazier

These scenarios have progressed from the realm of the imagination to reality, especially as cities worldwide race to prioritize sustainable structures that mitigate the impacts of global warming and create healthier work and home environments. Meanwhile, myriad players, including attorneys, are finding solutions that put a sustainable and healthier future increasingly within reach.

Brooklyn Law School has been prescient about sustainability; classes on the topic are now in their 14th year. Over the summer, the Introduction to Sustainability & Future Cities Boot Camp united professionals, alumni, and students to share ideas, knowledge, and experiences. Discussions at the event, as well as interviews with faculty and alumni afterward, revealed that the rise of green cities—and towns—is happening now.

The Challenges and Opportunities in Sustainability

“The built environment is responsible today for about 50 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions,” said Maria Aiolova, global principal of the AECOM Innovation Laboratory. “That [includes] the energy and materials we use.”

That is why entrepreneurial research groups and educational institutions are researching technological innovations in building materials and smart systems to bolster energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions. Architects, designers, builders, and owners are collaborating on sustainable outcomes. Public and private efforts to expedite economic and community development through sustainable infrastructure are on the rise. Another expediting factor is the pandemic, which has changed the way people think about indoor airflow and work-friendly space.

“The new generation is demanding a healthier environment in which to work and live,” said Calvin Lee ’10, director and senior counsel at WeWork.

Courtesy of Baxt Ingui Architects

For professionals in finance, land use, and the built environment, staying abreast of the sustainability-related legal issues is vital. For attorneys focused on real estate, expertise in this burgeoning field is invaluable and might include construction contracts and applying for LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, negotiating green leases and vendor agreements, and addressing compliance issues for companies with SEC-directed Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards.

“As an attorney, you can take a leadership role, especially in project finance and in the world of public-private partnerships, whether you’re representing the designer, the design-builder, or the special-purpose entity that is formed for purposes of developing a project,” said Nicole DeNamur, Seattle attorney and owner of consultancy Sustainable Strategies. “There is an opportunity for legal to be at the nexus of that network of contracts, to really have an outsized impact on developing these projects.”

Through its clinical work, expanding programs, and new partnerships, Brooklyn Law School is building on its history in the field—with law professors leading the way, such as Professor of Practice and Adjunct Professor Richard J. Sobelsohn ’98, among the first New York City attorneys to gain LEED AP (accredited professional) status and the first to attain Green Globes Professional (GGP) certification, and Director of Graduate Programs and Adjunct Professor John Rudikoff ’06.

Back in 2009, Sobelsohn joined the Law School to teach Legal Issues Affecting Sustainable Buildings, the first law school class among its New York City peers to explore sustainable real estate. The initial dearth of related case law and legislation on green buildings is no longer an issue for Sobelsohn, who now updates his curriculum to keep pace, as growing concerns over climate change and its effects have dramatically increased sustainability regulations and legislation.

“There are 33 states that either have or are looking at climate legislation and establishing goals that are then filtered down to U.S. cities,” said E. Gail Suchman, an ESG attorney and partner at Sheppard Mullin. She pointed to Washington, D.C.’s 2018 Clean Energy Omnibus Amendment Act; Denver, whose energy and building performance standards are part of its 80 x 50 Climate Action Plan; and New York City’s Climate Mobilization Act of 2019, whose goal is to reduce emissions from the city’s largest buildings by 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050.

There are also sustainability-related funds in the 2021 federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which includes approximately $370 billion in clean energy and climate investments over the next 10 years. Yet, says Stephen Del Percio, vice president and assistant general counsel at AECOM, “there is still a huge funding gap in terms of how we maintain existing infrastructure assets, let alone build the new ones to face the challenges of the 21st century. Public-private partnerships can help bridge that gap.”

Alumni Changing the Landscape

“Fighting the impact of climate change is not just about ideas,” said Carone. “It’s about action, and it’s happening right now.”

Many Brooklyn alumni have successfully created careers in the sustainable building space, including Silverstein Properties chair Larry A. Silverstein ’55. In 1980, his real estate development firm installed the first cogeneration system in a New York City office building, at its 11 West 42nd St. property. It achieved Energy Star certification for all its office buildings and rebuilt the World Trade Center (WTC) site after 9/11. Three of Silverstein’s WTC buildings are LEED Gold certified, and in 2021, New York State selected his firm as a partner in the “Empire Building Challenge,” an initiative to establish public-private partnerships with leading developers to usher in the next generation of high-rise, low-carbon buildings to combat climate change. “Larry has always been paying attention to sustainability,” Sobelsohn said. “The foresight he had and has makes a lot of sense.”

jackson has built his practice “on the waterfront,” helping revitalize former industrial spaces and neighborhoods.

Transforming the Workplace with Green Leases

Mark Jackson ’11, general counsel and vice president of Industry City, says collaboration is key for green clauses in commercial leases. “Environmentally conscious lease provisions are in many cases agreements between landlords and tenants to collaborate to reduce the carbon footprint of the building,” Jackson said. “That may include assurances that the landlord is taking smart steps like buying renewable energy or allowing tenants to do the same on their end.”

Green lease provisions may also ensure the tenants’ safety, health, and well-being through considerations such as improved ventilation and heat pump systems, or even visual access to landscaped outdoor space. Furthermore, the requirements of the city’s Climate Mobilization Act, Jackson adds, will make such landlord-tenant partnerships even more crucial.

Jackson, who studied architecture and worked in construction management before law, has long had a keen interest in green building practices.

While assistant general counsel for the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corp. in its transformation of 1.4 million square feet of former military space into new manufacturing and emerging business spaces, Jackson worked alongside alumni Richard Drucker ’67, senior vice president, and Martin Banker ’72, vice president and deputy general counsel. Jackson is especially proud of his work with one tenant, the Brooklyn Grange, which built a community-supported working farm on top of one building at the Navy Yard, thanks in part to a grant from the NYC Department of Environmental Protection.

“It was an amenity, an efficiency measure, a marketing story for the Navy Yard, a convener [for other tenants], and had financial benefit,” he said.

Later, as in-house counsel and commercial leasing director for real estate developer Two Trees Management Co., Jackson negotiated a ground lease for energy network developer Brooklyn Microgrid, which is using its two-acre site in Gowanus, Brooklyn, to develop a battery storage facility with solar panels. The battery storage system will be charged during off-peak hours and sell back to the grid during peak hours, thus reducing strain on the electrical grid. “The benefit for us was access to the battery storage as a resiliency measure, and they partnered with us in a battery charging station for vehicles in the parking lot—a great example of hybrid use,” Jackson said.

The key for attorneys in negotiating green leases? “You can’t draft a common-sense document for all parties until you understand how it’s going to be used—the logistics involved, the spatial requirements, how the critical path of construction works, and how it works in real life,” Jackson said. “When you’re presented with a big scope of work, the attorney is the last line of defense in getting it accomplished.”

Building for Resiliency

As former in-house counsel to the New York City Department of Design and Construction, John has been a key industry voice, drafting license and utility agreements and solicitation documents, and handling general compliance and procurement for some of the agency’s trickiest projects, including the 2015 Build It Back program, which coordinated repairs, rebuilding, and home improvements after Superstorm Sandy. She also worked on the newly under construction Coastal Resiliency Program, a green infrastructure project designed to protect Lower Manhattan from rising sea levels and coastal storms.

Working on complex transactions and commercial litigation with Zetlin & De Chiara clients has given John another deep dive into sustainable construction issues. “It’s great to see the city’s progressive push toward green building and the regulations to push private industry, and to be working with owners and vendors, designers and contractors on how they address them and best manage the risks and distribute those among the parties,” John said.

“For me, contracts are like a craft,” added John, a painting and jewelry design student before switching to liberal arts and law. “It’s a functional document that has to work like a clock or computer program.” She discovered the art and precision of contracts in Professor of Law Emeritus Arthur Pinto’s contracts class and the allure of construction from Professor Debra Bechtel, who teaches community development and real estate law, and influenced her career choice. “Real estate and construction in general, and property development of communities that add to the landscape of the city, wherever you’re living, create a special connection with your work,” she said.

JOHN has made coastal resiliency and design-build projects her legal forté.

Developing the Economy, Engaging the Community

“We have an important role in keeping the community’s trust, to analyze the impact on neighborhoods and the opportunities for local businesses and jobs,” Lee Romero said.

In coastal Maine, the Karp Strategies team worked on offshore wind development with the Governor’s Energy Office, performing workforce and supply-chain analysis and research, and developing recommendations to create jobs for existing businesses, coax in wind-related businesses from out of state, and encourage equity and support for small, minority-owned, and disadvantaged business enterprises. In Red Hook, Brooklyn, where Karp Strategies is working with the New York City Department of Design and Construction and global engineering consulting firm NV5 on coastal resiliency measures, the team does outreach with local schoolchildren, “getting them excited about ways infrastructure can impact their community, protecting it against floods resulting from climate change. That also gets their families involved,” Lee Romero said.

The advice of his Brooklyn Law School mentor Adjunct Professor of Law Leonard Wasserman ’72, who was also special real estate counsel for NYCEDC, has resonated with Lee Romero throughout his career: “He inculcated the idea that our work was about, as he said, ‘shaping the urban environment’ and how to do it right through best practices,” he said.

Real estate law can’t be viewed through the “old-school lens of buying and selling of property and of conducting transactions,” Lee Romero added.

“That’s all part of our work, but increasingly, regulations are pushing the private sector to innovate, for development managers to think of sustainable, cost-effective solutions, like converting to clean energy,” he said. “We can’t think of it as yesterday’s practice; it’s evolving.”

Innovating With RPI

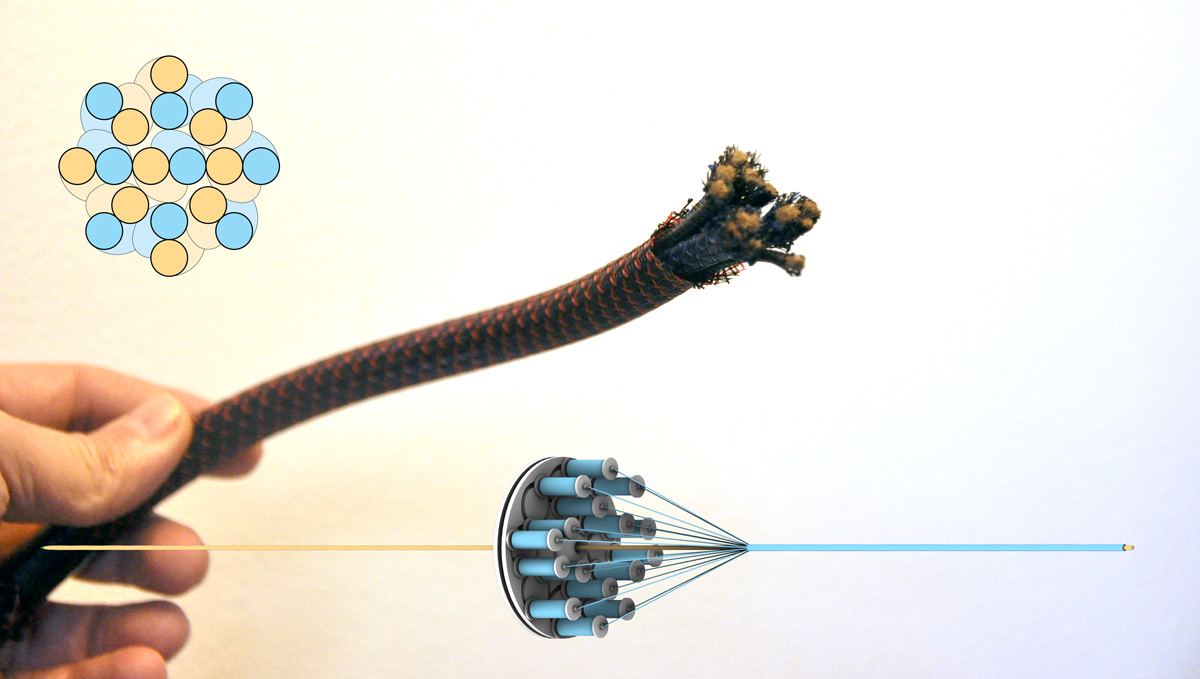

Brooklyn Law School is untangling those very issues as an academic and legal partner of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in its Institute for Energy, the Built Environment, and Smart Systems (EBESS), which also includes engineering, architecture, and electronics partners. EBESS fuses architectural design and engineering to create sustainable infrastructure that is both climate-resilient and a net-zero producer of greenhouse gases, using renewable energy systems, sentient building platforms, and new materials.

The seed to unite the two schools on the project was planted in 2018 by Wanda Denson-Low ’81, the forward-thinking vice chair of the board at RPI and a retired senior vice president at Boeing. RPI’s then-president Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson, a renowned physicist, shared her enthusiasm.

“CASE and EBESS are standouts in the field of sustainability,” says Director of Graduate Programs and Adjunct Professor of Law John Rudikoff ’06, who, with Professor of Practice and Adjunct Professor of Law Richard J. Sobelsohn ’98, is leading the Law School in the EBESS partnership. “They’re developing and incubating high-tech sensors to create energy efficiency and newer systems of engineered living material, to fabricate green roofs and green walls, or building materials that can reduce carbon impact.”

The legal implications of the technology are myriad, says Rudikoff. “They involve navigating building codes, which specify which materials can and cannot be used. Or understanding the privacy and security implications of smart systems that track movement, ventilation, and lighting,” he added. “What are the liability issues?”

She encourages both law students and attorneys with a commitment to sustainability to further explore the field.

“Where you’re going to find innovation is when you color outside the traditional lines. As lawyers, we all have belief systems, and you can always use law to promote the things you believe in,” Denson-Low said. “And Brooklyn Law School has always been a place where a lot of innovation happens.”